How To Cross Tune Your Fiddle

Cross tuning a fiddle is common practice in many traditions around the world, but often produces a bit of apprehension and confusion with musicians who are most comfortable with the ‘standard’ tuning of GDAE. Let’s demystify the process so you can begin to enjoy the benefits and fun idiosyncrasies of each tuning.

Quite a few students ask me why I like re-tuning my fiddles, and wonder if it’s really worth the ‘bother’.

Why not just play everything in standard tuning?

Each tuning is used for a specific key, which often provides an open string drone above and/or below the melody. That’s not always the case with standard tuning! All the open strings vibrating in sympathy or as drones and double stops give an amazing resonance to your tone.

Also, re-tuning your fiddle to a key is kind of like a guitar or banjo player using a capo. Certain keys and their handshapes just feel better in our hands, so why not take advantage of those handshapes in other keys by re-tuning?

*Sidenote: If you’re unsure of what a capo does, or if you do but could still use some help decoding a guitarist’s handshapes - they can help you understand and hear chords for jamming and other cool things like double stops, improvising, etc.- here is a post to explain all that.

Okay, back on track. Let’s tune.

I recognize that you might be scared. I mean, you want your fiddle to be in tune and playable! But it’s going to be okay. Some people worry that their instrument might explode. Re-tuning your fiddle isn’t bad for it - and way less ‘dangerous’ than leaving your fiddle in the sun, a hot or cold vehicle, dropping it, etc. If something goes really wrong, there are luthiers who can help. If you break a string, you can replace it. (Let’s face it, strings can break when you’re learning to tune in standard, so as long as you’re careful and tune slowly, you’re probably gonna be just fine). If you understand the mechanics of tuning, and practice tuning to different keys/combinations, you’ll get better at it.

I’m assuming that if you’re interested in re-tuning your fiddle, you’re probably already familiar with tuning your instrument in standard tuning. BUT, just in case you stumbled upon this post for help tuning, or if your teacher often just tunes for you, let’s go over the mechanics of tuning.

These points are helpful for standard or cross tuning.

Ninety-seven point six percent* of all fiddles have friction pegs. This means that the wood of the peg is caught by the friction against the wood of the pegbox. Wood expands and contracts with changes in temperature, humidity, and tension. SO, if all of a sudden the temperature outside drops, your house gets really cold and you then turn on the heat, the wood in your instrument will shrink. That means there’s less friction to hold your pegs in place, so they might slip or even pop. If this happens to one string, the tension of the pegbox has gone haywire and that will probably negatively affect the other strings. You can try to prevent all this havoc on your instrument by protecting it from these kinds of extreme changes in temperature and humidity.

This whole tuning system is very different from machine head or geared pegs. When you turn a peg on a guitar, the gears hold the string in a specific position. While fine-tuning is still necessary, the tension and friction factors aren’t paramount to keeping your instrument playable. People who are new to tuning a fiddle often turn a peg to the desired pitch and let go, watching the peg slip back (or worse, below) their starting point. Instead, fiddlers need to turn and push simultaneously. This is physically challenging, especially if you’re also learning how to hear/understand pitch.

If you’re new to tuning/re-tuning your fiddle, I recommend starting to tune with your instrument in your lap instead of under your chin.

Hold your fiddle upright between your knees, facing you. Use one hand on a peg and the other to pluck the string you’re tuning, while you’re turning the peg. This way you can hear how far you’re turning your peg and you won’t go too far and past your pitch. At first, I tell students to get each string ‘sorta in tune’. I give an analogy of a dartboard: the bullseye is the center of the pitch, in its true form. When you’re making that first pass of tuning each string, you want to get each string (dart) at least on your dartboard. So if you’re trying to tune your string to an A, and you’ve tuned your string to a G, you’ve missed the dartboard. You’ve got to get your string to at least an A-ish note. I tell my students to aim for ‘sorta in tune’ at first because each string affects the overall tension of the instrument. So if you spend time getting your A string PERFECTLY in tune (the bullseye) but your other strings are completely off, the A string will just go out of whack again after you adjust the other strings. So go through and get each string to a note that’s ‘on the dartboard’ and then go back through each string and tune right to the bullseye. This will probably take a couple of passes through each string. As you become more fluent in tuning your instrument, you might be able to hit the bullseye on your first attempt, like it’s NBD. Good for you. If you’re not there yet, it’s okay. It takes time.

A tuner or drone can be most helpful if you’re unsure of how far to move the peg, but the best thing is to use your voice and your instrument to train your ear. If you can match pitch, re-tuning your instrument gets a lot easier.

Would you like help with matching pitch/singing/playing?

There are tips in this post:

If your instrument has fine tuners, you’ll be able to use them to tune the final bit towards a bullseye. Fine tuners are awesome, but not necessary. And they won’t help you if your string isn’t even on the dartboard. Gotta use your pegs anyway.

Once you think you’re as close to in tune as you can be with tuning in your lap and plucking your strings, go to playing position and use your bow while you tune your strings. Play two strings at a time and use long, consistent bow strokes so you can listen to the vibrations and sound waves of the strings. If the string(s) are out of tune, the sound waves will knock against one another and you’ll hear an almost rhythmic beat. When the strings are in tune to each other, the sound waves roll together and you can hear your instrument blossom with the vibrations. It’s an amazing experience - you can hear and feel and see it all happening.

Alright. So those tips are relevant and necessary for ANY tuning. Let’s start to explore three of the most common tunings used in Old Time fiddle traditions.

Cross Tuning in A

This tuning lifts your bottom two strings up a full step. This moves your G string up to an A, and your D string up to an E. From lowest to highest, you’ll now have AEAE instead of the ‘standard’ GDAE. This tuning is used for the key of A. To find tunes that are primarily played in Cross A, head to Slippery Hill’s search page and you’ll find over 400 tunes. BTW, Slippery Hill is a fantastic site for source recordings. If you’re unfamiliar with source recordings, here’s a fabulous post written by musician/person extraordinaire Brittany Haas.

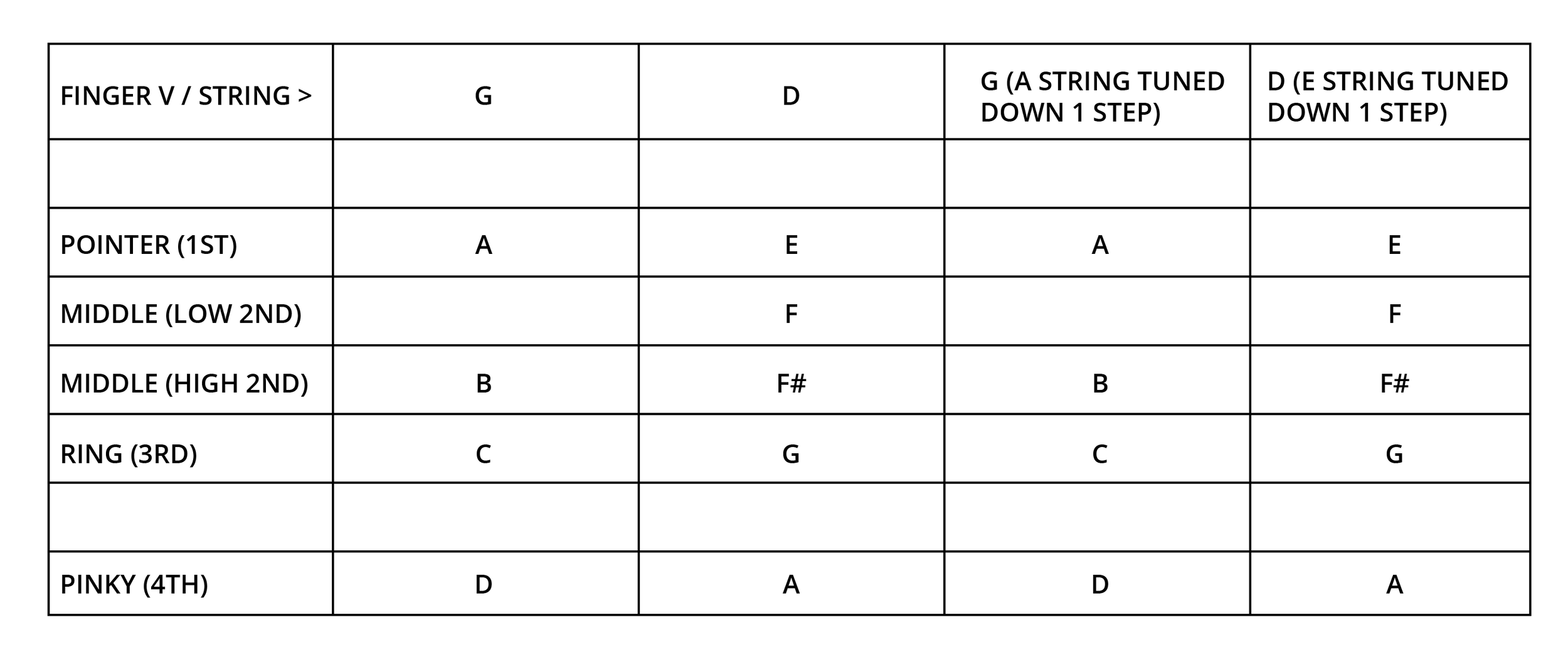

Okay, Here’s a chart of your fingerboard in Cross A tuning.

Here’s a video of me tuning my fiddle from standard into Cross A, playing a scale, pointing out some cool aspects of the tuning like octaves and unisons, and then re-tuning to standard. I hope you’ll play along and before you tune back to standard, explore your fiddle. Try playing tunes you already know in the key of A in this new-to-you tuning. Find the common 1, 4, 5, maybe even the 6minor and flat7 chords. These will feel different than they felt in standard- sometimes they are easier, sometimes they are odd.

Wondering what 1, 4, 5, 6m and b7 chords are and how they function? I have a huge beautiful book on these chords in the Key of A. Granted, it’s all mapped out in standard tuning, but all the chord spellings and the explanations of how they function is the same as Cross A.

Digital book filled with harmonic information for the keys of A Major and A minor. Including twenty (20) arpeggios and chords voiced all over your fingerboard in first position.

Cross Tuning in G

Sometimes, teachers recommend starting with Cross G instead of Cross A, because you tune your top two strings down a step and this means you’re less likely to break a string (in Cross A you’re tuning the bottom two up and the strings are under a higher amount of tension, so they *might* break). Plus, the relationship/intervals between the strings in Cross G is the same as the intervals between the strings in Cross A, so the hand shapes and fingerings are the same in relation to the key. It’s just the sound (notes) that are produced are different - again, very much the same idea as a capo.

In this tuning, you keep your G and D strings as is and lower your A string down a step to G and lower your E string down to a D. From lowest to highest you now have GDGD. This tuning is used for the key of G.

Here’s a chart of your fingerboard in Cross G.

Here’s a video of me tuning my fiddle from standard into Cross G, playing a scale, pointing out some cool aspects of the tuning like octaves and unisons - you’ll notice they are the same as Cross A - and then re-tuning to standard. Again, I hope you’ll explore your fiddle. Try playing tunes you already know in the key of G in this new-to-you tuning. Find the common 1, 4, 5, chords. Refer to Slippery Hill for more tunes in this tuning, and remember you can play all your AEAE tunes in this tuning - they’ll feel the same.

High Bass Tuning

One more tuning for this post. Maybe we should have a Part 2 with more tunings? Email [email protected] if you would find a 2nd part helpful.

High Bass tuning lifts the bass string (G) to an A. From lowest to highest your strings are tuned ADAE. This tuning is used for the key of D.

Here’s a map of your fingerboard in High Bass.

Here’s a video of me tuning my fiddle from standard to High Bass, playing a scale, pointing out the unisons and octaves, and then re-tuning to standard. Try playing tunes in the key of D you already know, and then check out Slippery Hill for more tunes in this tuning. You may notice that some D tunes don't even go on your lowest string at all in the melody, but tuning it up to A will give you that extra ringy sound whether you use it to drone or not.

If you’d like more help on chords in the keys of G and D, I have a handy little chord book (maps in standard, chord spellings and functions apply to any tuning).

A 50 page workbook for instruments tuned in 5ths.

A book designed to guide you through building and voicing chords on your instrument.

My online curriculum also includes a Bonus Module on Cross A, with lots of videos teaching the scales and chords, and a few tunes: Walk Along John to Kansas, Breaking Up Christmas, and Booth Shot Lincoln. I break each tune down phrase by phrase, teach the chords, and show you how to jam. You can find more information on my curriculum here.

Alrighty, that’s quite a bit to digest at once. Good luck tuning/re-tuning your instrument. It will be worth it! Once you hear all the glory and goodness of a fully resonating fiddle, you’ll be hooked.

Happy Jamming,

xoL

*I have not researched this number, but it seems very probable and this statistic was meant to make you giggle.